Disclaimer: This is part of my notes on AI research papers. I do this to learn and communicate what I understand. Feel free to comment if you have any suggestion, that would be very much appreciated.

The following post is a comment on the paper SLIDE: In Defense of Smart Algorithms over Hardware Acceleration for Large-Scale Deep Learning Systems by Beidi Chen, Tharun Medini, James Farwell, Sameh Gobriel, Charlie Tai and Anshumali Shrivastava, from Rice University and Intel Corporation.

To get around the costly computations associated with large models and data, the community is increasingly investing in specialized hardware for model training. However, such machines are expensive and hard to generalize to a multitude of tasks. In this paper, the authors propose SLIDE (Sub-Linear Deep learning Engine) that uniquely blends smart randomized algorithms, with multi-core parallelism and workload optimization. The authors show that SLIDE on a 44-core CPU, drastically reduces the computations during both training (3.5 times faster) and inference outperforming an optimized implementation of Tensorflow on a Tesla V100 GPU.

They explore the idea of adaptative sparzity. The idea stems from the fact that we can accurately train neural networks by selectively sparsifying most of the neurons, based on their activation, during every gradient update. However, this technique does not directly lead to computational savings. To achieve that, they employ Locality Sensitive Hash (LSH) tables to identify a sparse neurons efficiently during each step.

Locality Sensivite Hashing

LSH is a family of functions with the property that similar input objects in the domain of these functions have a higher probability of colliding in the range space than non-similar ones.

It is shown that having an LSH family for a given similarity measure, is sufficient for efficiently solving nearest-neighbor search in sub-linear time.

LSH Algorithm

The LSH algorithm uses two parameters $(K, L)$. Authors contruct $L$ independent hash tables, each of which has a meta-hash function $H$ that is formed by concatenating $K$ random independent hash functions. Given a query, we collect one bucket of each table and return the union of all $L$ buckets, which reduces the number of false negatives. Only valid nearest-neighbor items are likely to match all $K$ hash values for a given query, thus $H$ reduces the number of false positives:

- Pre-processing phase: Construct $L$ hash tables, storing the pointers to the data elements.

- Query phase: Given a query $Q$, search for its nearest-neighbors by querying all $L$ hash tables and returning the union of all $L$ buckets.

LSH for Estimation and Sampling

It turns out that taking a few hash buckets (as low as 1) is sufficient for adaptive sampling. Given a collection of vectors $\mathcal{C}$ and a query $Q$, we get a candidate set $S$ from a $(K,L)$-LSH algorithm. Every element $x_i \in \mathcal{C}$ gets sampled into $S$ with probability $p_i$, where $p_i$ is a monotonically inicreasing function of $Q \cdot x_i$. Thus, we can pay on-time linear cost of preprocessing $\mathcal{C}$ into hash tables, and adaptive sampling for quary $Q$ only requires few hash lookups.

SLIDE Algorithm

- Initialization: Every layer object contains a list of neurons and a set size $L$ of LSH sampling hash tables. Each hash table contains $K$ LSH hash functions and the ids of the neurons that are hashed into the buckets. The weights of the network are initialized randomly.

If $h_i^l$ is the $i$-th hash function in the $l$-th layer, the hash value of the $j$-th neuron’s weights in the $l$-th layer is denoted by $h_i^l(\omega_l^j)$. After compunting the hash values for the $K$ hash functions, the id $j$ of the neuron is inserted into the corresponding buckets of the hash table in the $l$-th layer. This is done for all neurons in all layers. Note that this is easily parallelizable.

- Sparse Feed-Forward Pass with Hash Table Sampling: The input of each layer $\textbf{x}_l$ is fed into the hash functions $h_i^l$ to get the hash values. The active neurons are then sampled by querying the has tables and retriving the ids from the matching buckets. Only the activations of active neurons are computed and passed as inputs to the next layer. The other activations are treated as zeros and are never computed.

Efficiently sampling the active neurons is crucial for the performance of the algorithm. If $\beta_l$ is the number of active neuros we target to retrive at layer $l$, authors propose three strategies to sample the active neurons:

- Vanilla Sampling: Randomly choose one of the $L$ hash tables and query the corresponding bucket. Keep repeating this process until $\beta_l$ neurons are sampled.

- Top-$\beta$ Sampling: Aggregate the number of neurons in all buckets of all hash tables and select the top $\beta_l$ neurons.

- Hard Thresholding: Set a threshold $m$ and proceed similarly as in Top-$\beta$ Sampling, but only select the neurons that have more than $m$ neurons in their bucket, thus avoiding the need to query all hash tables.

Sparse Backpropagation or Gradient Update: Classical backpropagation layer-by-layer is used to compute the gradients of the loss function with respect to the weights of the network, rather than vector-based backpropagation. As a result, non-active neurons are never accessed and the computation cost is only proportional to the number of active neurons.

Update Hash Tables: After modifying the weights of the network, the hash values of the neurons are recomputed and the hash tables are updated accordingly. This can be computationally expensive, but authors propose some simple strategies to reduce the cost:

- Exponentially Delayed Update: Instead of updating the hash tables after every gradient update, the authors propose to update the hash tables after a certain number of gradient updates. Starting with a delay of $T_0$ iterations for the update, authors apply exponential decay to the delay, i.e. the $t$-th update occurs after $\sum_{i=0}^{t-1} T_0e^{-\lambda i}$ iterations, where $\lambda$ is a decay factor.

- Replace Policy: Buckets have a maximum capacity. To decide which neuron to replace autors propose to policies. On one hand, the Reservoir Policy that uses Vitters reservoir sampling. On the other hand, the First-In-First-Out (FIFO) Policy that replaces the oldest neuron in the bucket.

- OpenMP Parallelization across a Batch: To ensure the independence of computation across different threads, every neuron stores three additional arrays, each of whose length is equal to the batch size. These arrays keep track of the input specific activations, gradients and active input neurons. Authors claim that is memory overhead is negligible for CPUs. The extreme sparsity and randomness in gradient updates allow to asynchronously parallelize the computation of the gradients across the batch, without a considerable amount of overlapping updates.

Details of Hash Functions and Hash Tables

There is a trade-off between efficiency of retrieving active neuros and the quality of the retrived ones. Authors propose using four different types of hash functions from LSH family Simhash, WTA hash, DWTA hash and Minhash.

Experimental Results

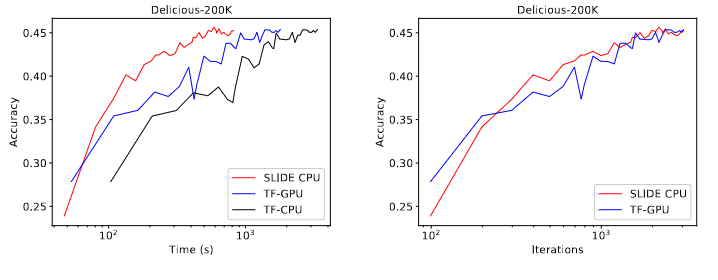

Comparison against SLIDE, TF-GPU and TF-CPU. Note that the time required for convergence in SLIDE is the lowest, while comparing against the number of iterations the behaviour looks identical, which suggests that SLIDE superiority is due to algorithm and implementation and not due to any optimizations tricks.

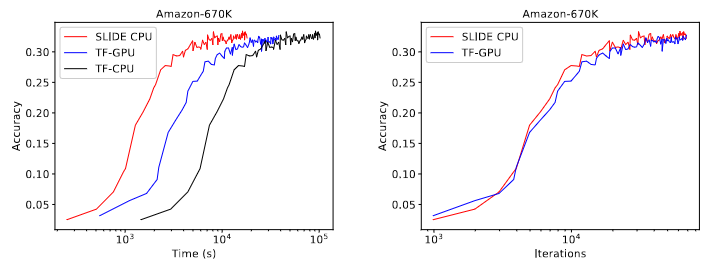

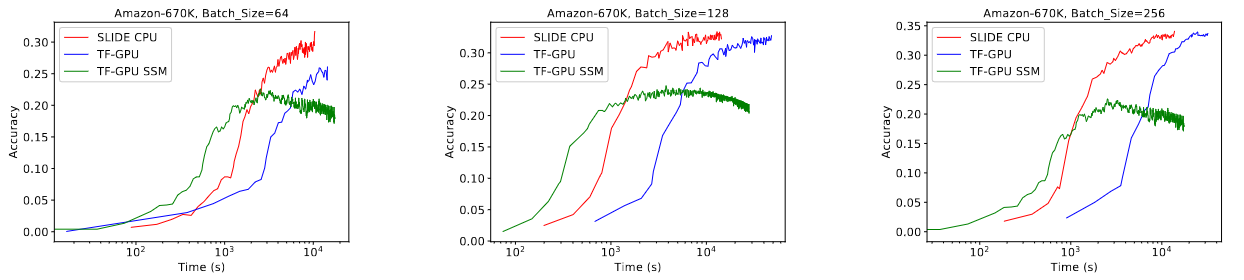

SLIDE outperforms the baselines at all batch sizes, and even the gap gets wider as batch size increases.

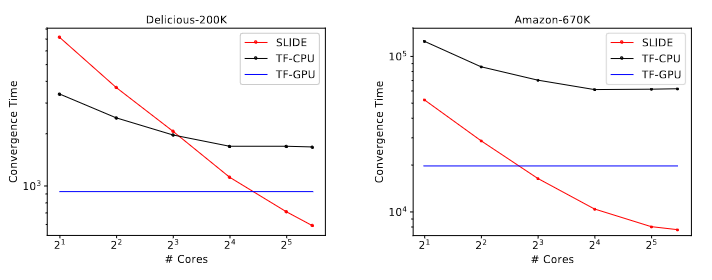

Comparison of performance gains with the number of CPU cores. Convergence time droops steeply for SLIDE as the number of cores grow.

Conclusion

SLIDE is a novel algorithm that combines smart randomized algorithms with the right data structures that allow asynchronous parallelization across a batch. The authors show that SLIDE outperforms 3.5 times faster than TF-GPU on a Tesla V100 GPU.

References

[1] Chen, B., Medini, T., Farwell, J., Gobriel, S., Tai, C., & Shrivastava, A. (2024). SLIDE: In Defense of Smart Algorithms over Hardware Acceleration for Large-Scale Deep Learning Systems. arXiv:1903.03129.